Heavy on the Joy

My most vivid childhood memories are those of my cousins and I running in Brooklyn’s summer heat—ferocious sweat frizzing our nappy coils. We knew nothing yet of relaxers and bonnets, waves and durags. We were too free to know anything beyond the exhilaration we experienced cooling off at fire hydrants, chasing Mister Softee for cartoon character popsicles with hard gum balls, slapping rubber handballs against the walls of abandoned fields, and playing freeze tag—skin begging to scrape the concrete. I remember on one of these days, how my great grandmother, Mama, would shift between a nervous rock in an old rocking chair, and a determined pace to check on me through the screen door. I remember the ways she would grab the ends of her blue plaid dress and rub her hands against the red kerchief tied to the front of her forehead (that’s where Tupac must’ve gotten the idea.) I remember how worry would wrinkle itself into her face and sag below her cheekbones. On days like this she would often plead for me to come back inside before I got hurt—urging my great grandfather to tell me the same. But I never saw the dangers of childhood freedoms, only the joy.

When I felt my cousin’s hand unfreeze me, I knew it was my moment to run as fast as I could. Chasing continuous joy, I darted down the block, full of speed and vigor and slid right into a hill of dirt—my knees kissing the asphalt like a player daring to make it to the base. I was bleeding, legs full of fire, my cousins running to offer help. It felt like torture—the embarrassment, of course—of losing the game, of falling in front of everyone, and of what I knew would come next. Papa, who was watching from the front door, pushed it open and told me to bring my backside inna di house. “Who don’t hear, must feel,” he reprimanded—a Jamaican proverb for hard headed children who chose not to take heed. In that moment I felt everything.

This was one of many Jamaican proverbs I would learn to live by. If my mother were reading this now, she would laugh at me mentioning the one about pig and his mouth—but I’ll hold onto that one because only life experiences could explain it. I was always aware of this duality of my identity—American born with a Jamaican family. Yet, it wasn’t until 2019 that I first verbally expressed that I was a first generation American. I moved from New York—a beautiful collage of the African Diaspora—to Georgia (a cultural difference I will explain soon).

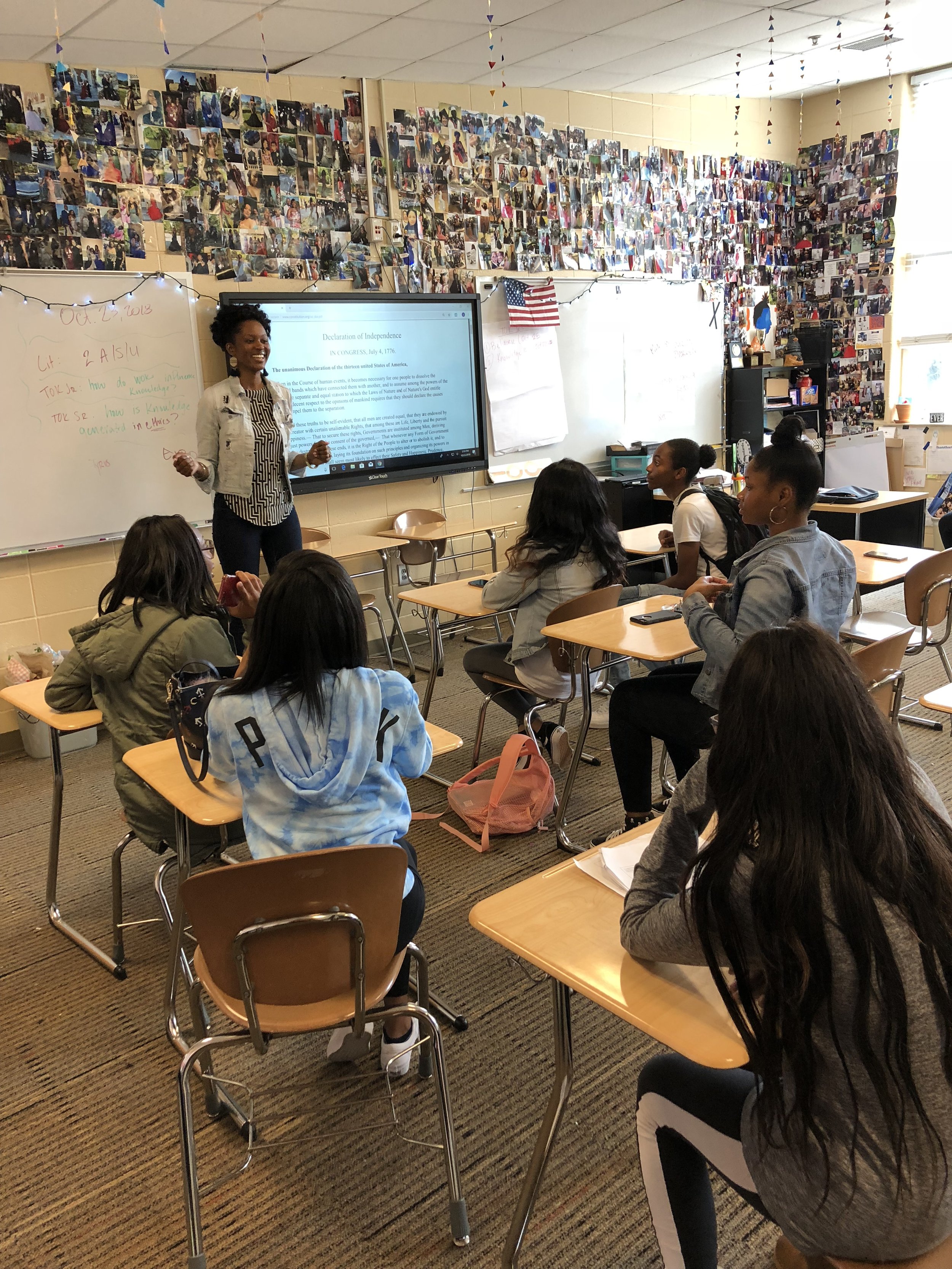

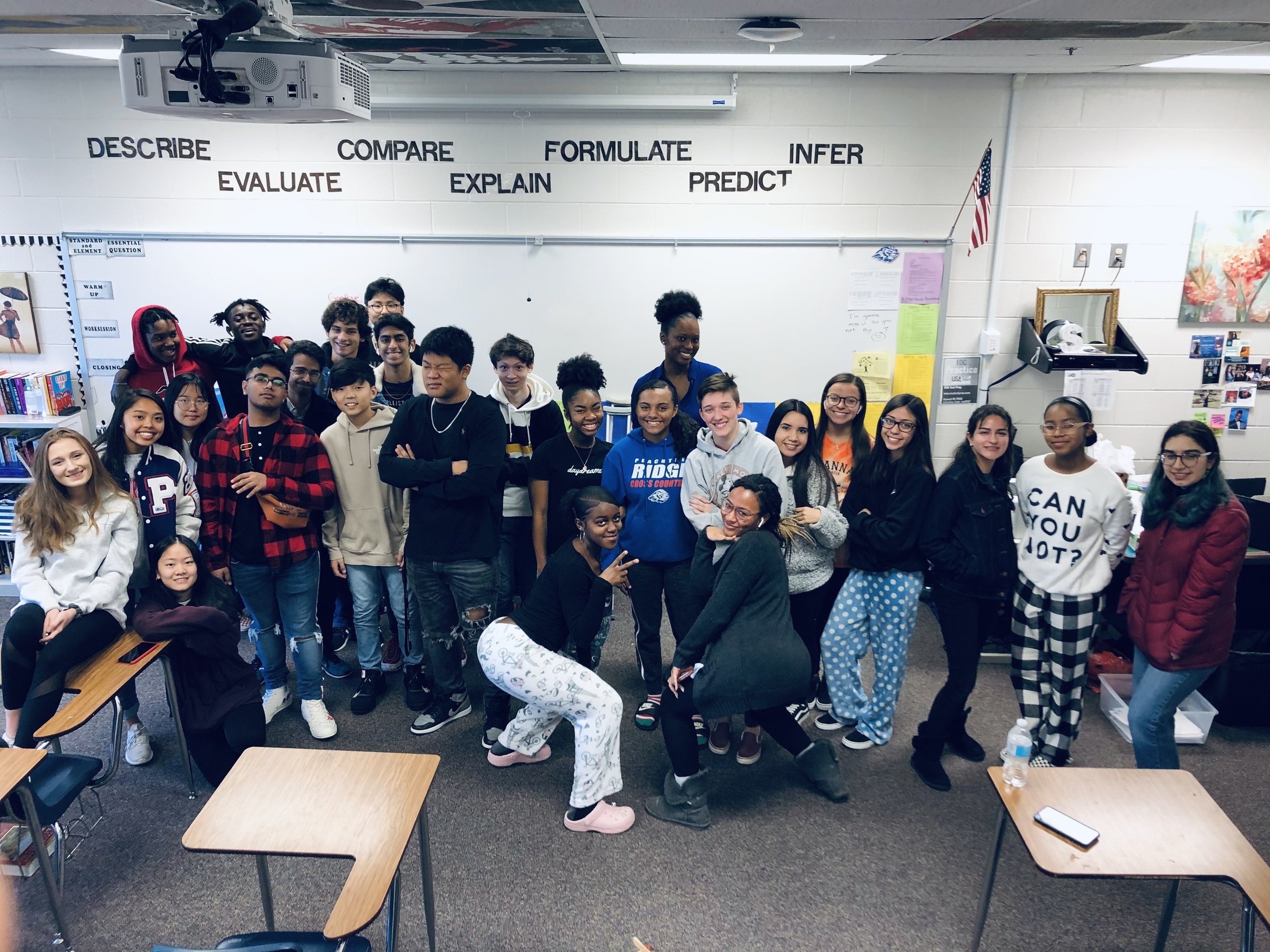

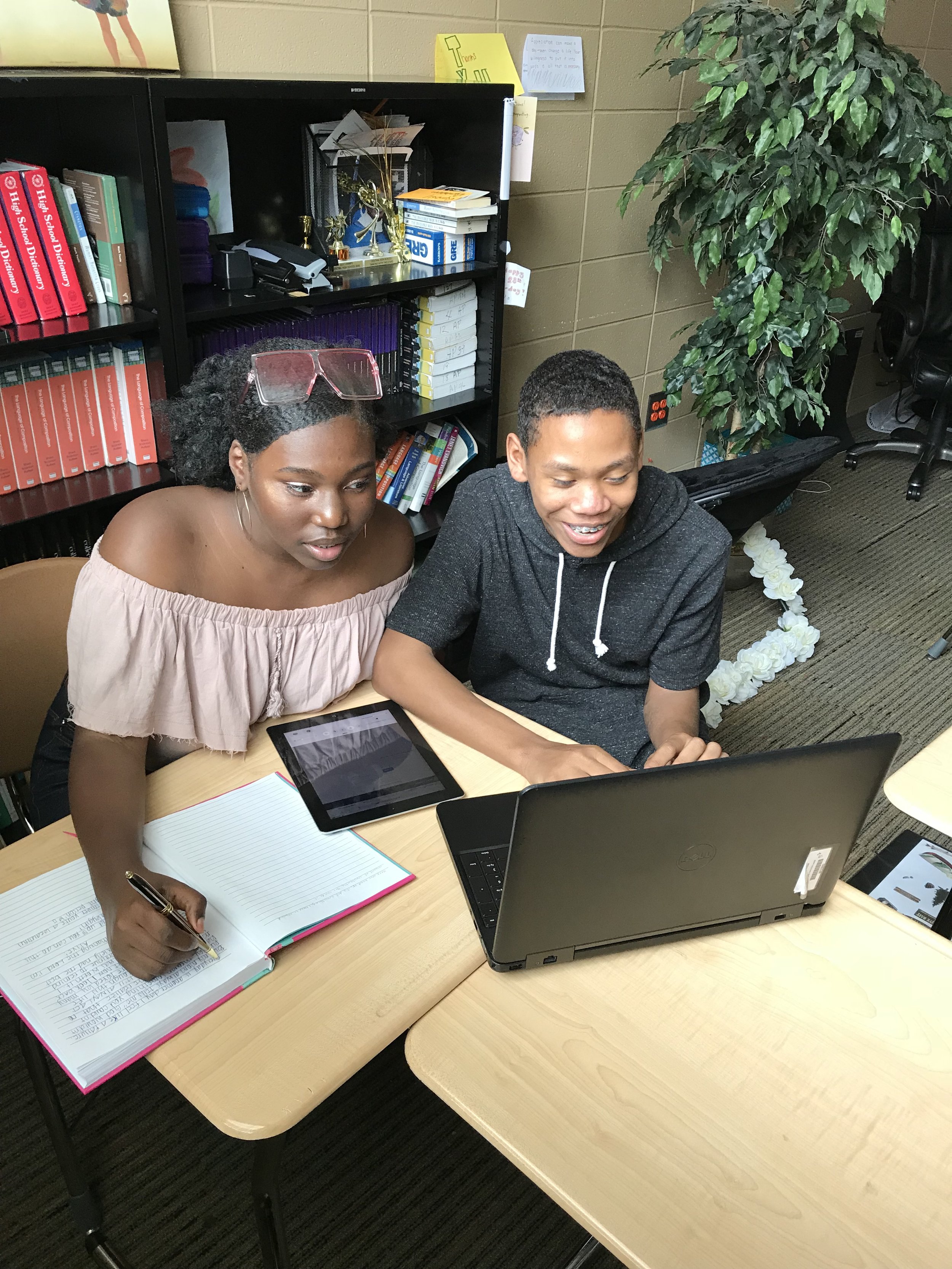

I attended Georgia State University—a decision I made heavily based on the fact that it was located in downtown Atlanta. I needed to feel and smell and walk a city space. In 2013, I started my career as an English Educator, teaching English Literature & Composition in high school. I felt invigorated (and exhausted) in the classroom, but I was right where I wanted to be. I loved teaching and providing space and opportunities for students to connect and see themselves reflected in the lessons, texts, activities, and modes of expression. I was inspired by the idea that we should bring our full authentic selves to academic spaces. I embraced what that meant for me and it made me a better teacher. I truly believed, as many have often said, that teaching is an act of love: self love and a love for your students.

Moving to a place so culturally unfamiliar was initially a challenge. In Brooklyn, my culture was celebrated through food, music, language, Labor Day parades, and subway performances. But Georgia was different and for years I performed this balancing act of constantly and proudly declaring my identity to some, while proving its authenticity to others. Outside of Brooklyn, I became “not New York enough”--whether it was a fleeting accent or my disdain for cold weather. I also wasn’t “really Jamaican” as I rarely entertained the “can you speak Jamaican” requests. This ongoing dance with identity surely influenced how I approached my lesson plans. I revered texts that offered opportunities for us to examine identity. In my personal reading, I loved to see myself and my experiences reflected in literature. I was drawn to audio, video, and visual art that told my story. Learning my identity and history became more fulfilling and gripping. Books were just as satiating as water. I was reading, researching, and eventually collecting stories from my own family.

I embarked on an Ancestry journey, hoping to learn more about my family’s history beyond Mama and Papa—to hear Jamaican childhood stories of playing dandy shandy and bull inna pen. I had no previous knowledge beyond those great grandparents. I scoured through hundreds of U.S. records before I remembered that my family had only immigrated to the U.S. in the 70s. When I started searching through Jamaican birth, death, and civil registries, my world expanded. The stories began to unfold. I began interviewing aunts, uncles, cousins, my grandmother, and my mom and dad. I had often heard the saying that Jamaicans are a proud people–and in this moment I was beaming with rightful pride and uncontainable joy. I’ve felt this as a Black woman reading Edwidge Danticat, Maya Angelou, and Ibi Zoboi, as a Black American reading Ta Nehisi Coates, Michelle Alexander, and Dr. Monique Morris, as a descendent of immigrants listening to Elizabeth Acevedo and Jamila Lyiscott. I felt these unique forms of joy both separately and simultaneously. The identities I’ve described above overlap and intersect and understanding and celebrating the complexity of that continues to be the highest form of self-reflection. That is my act of self-love–getting to learn and unlearn, accept and acknowledge the parts of myself.

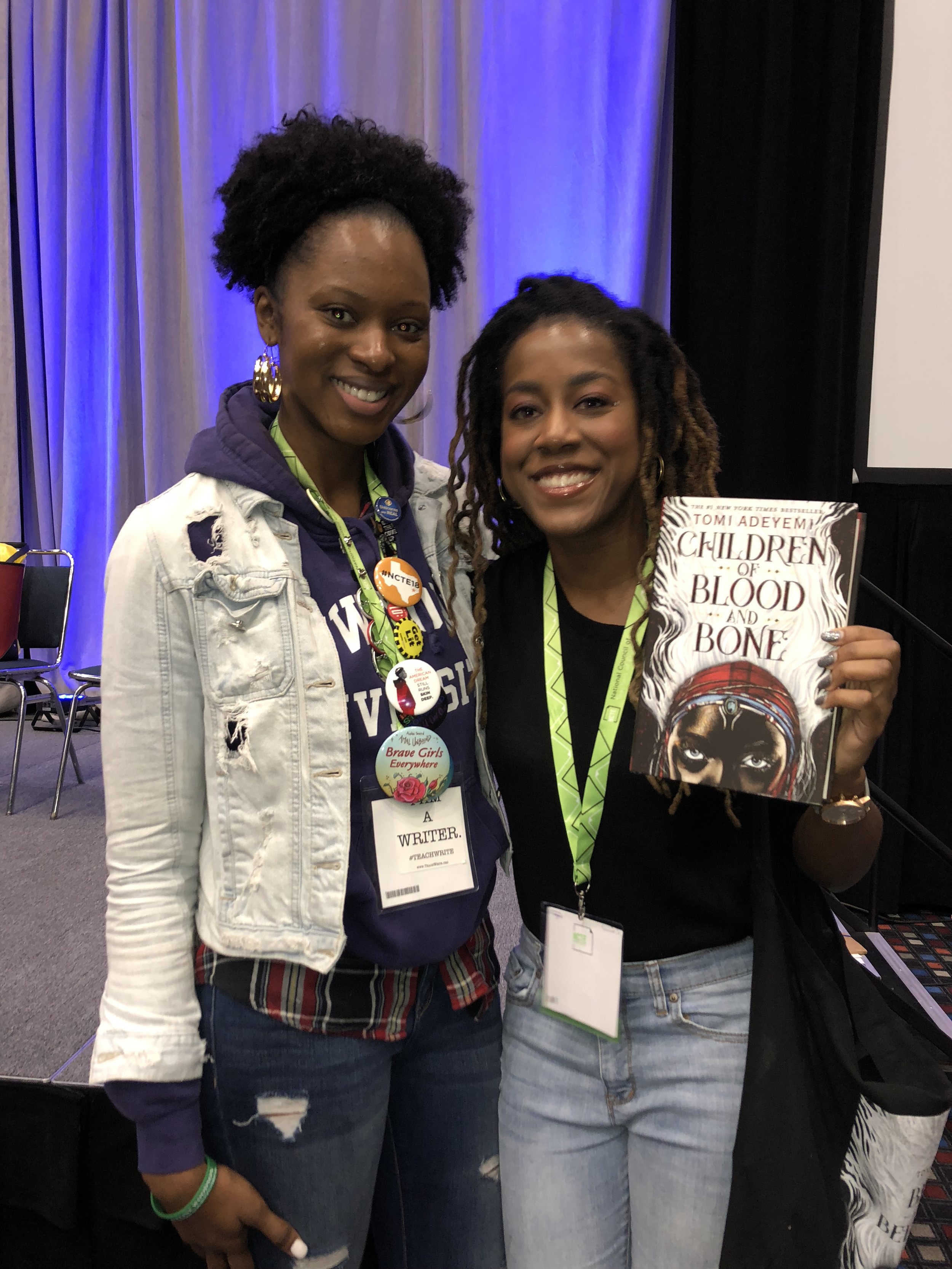

My love for my students would show itself in this way as well. I wanted to celebrate and affirm all parts of their identities because I have experienced the joy that comes with it. I know what it feels like to love and be proud of who you are–to see your culture, history, and story celebrated. So when we read Marlinda White-Kaulaity, Tommy Orange, Sherman Alexie, Gish Gen, Kelly Yang, Joan Didion, Victoria Aveyard, Kathryn Gonzalez, George M. Johnson, Danez Smith, Trevor Noah, Tomi Adeyemi, Sonia Sanchez, Yusef Salaam, Octavia Butler, Langston Hughes, Mohsin Hamid, Samira Ahmed, and many others, we are simply engaging in acts of love–for ourselves and others.

Love has always been my approach to things. I am intentional in the way that I love and experience joy and want joy for others. Joy is the freedom to be. Joy is laughter, movement, liberation, history, resistance, deep breaths, and storytelling. Joy is Mama and Papa, freeze tag, and digging for history. Joy is culture, music, and language. Joy is a curriculum that honors that. Joy is seeing yourself on the cover. Joy is writing yourself into the plot. Joy is identity, duality, intersectionality. Joy is race and gender and sexuality, and class, and education, and religion, and choice, and safety, and all the things they told us not to talk about–but writing about it anyway. Joy is what I am offering you today and hoping that you accept it. #HeavyOnTheJoy

This blog post is part of the #31DaysIBPOC Blog Series, a month-long movement to feature the voices of indigenous and teachers of color as writers and scholars. Please CLICK HERE to read yesterday’s blog post by Morgan Jackson (and be sure to check out the link at the end of each post to catch up on the rest of the blog series).